State of the Climate: Global Temperatures Throughout Mid-2023 Shatter Records 2025

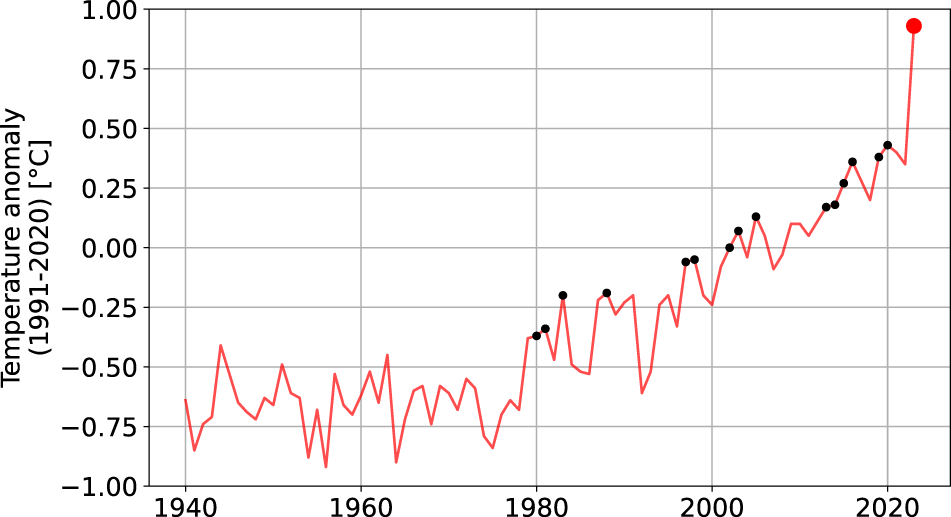

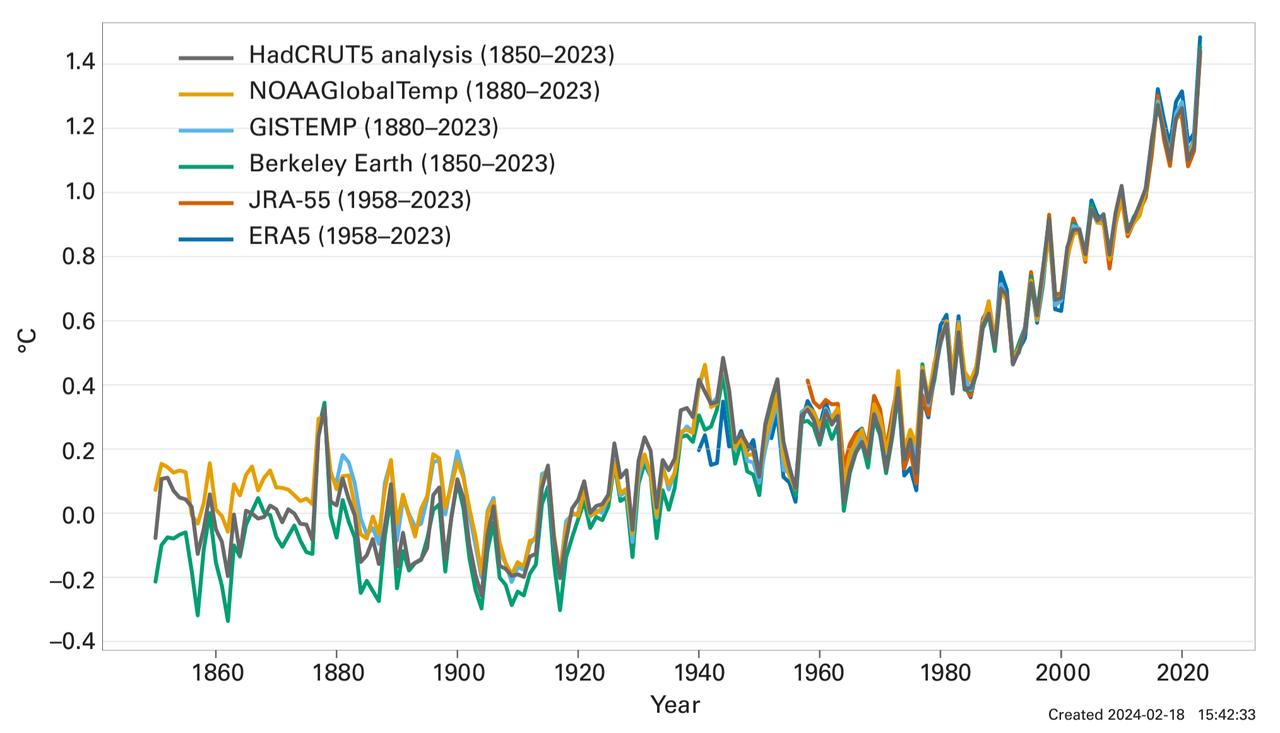

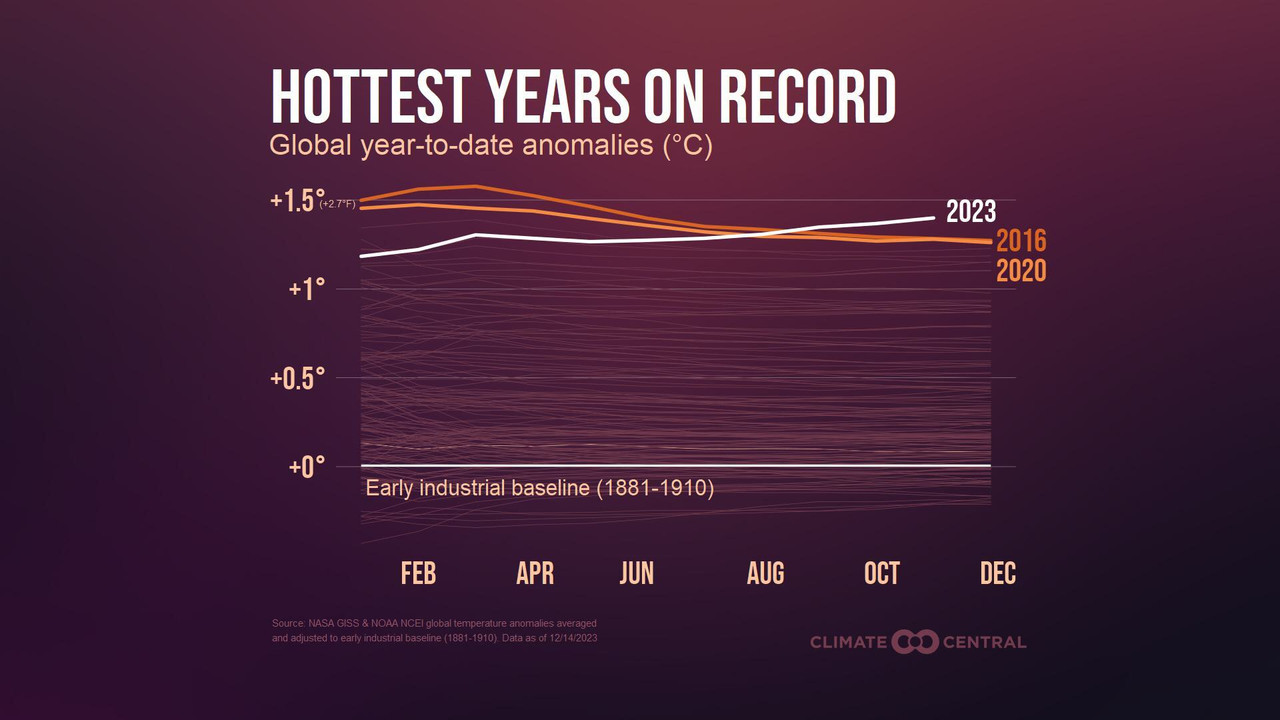

Monthly global temperature facts were broken for twelve successive months from June 2023 to May 2024. Almost a 12 months in the past today, July 6, 2023, become the warmest day on report for the whole planet with a global common temperature of 17.08 ranges Celsius (62.74°F); July 2023 became the warmest month on record globally. Averaging 1.8 ranges Celsius above the preindustrial average temperature, September 2023 became the globe’s maximum anomalously warm month.

If this wasn’t demanding sufficient, the significance of the jump in intense temperatures become also a file. For several months the worldwide temperature top handed the 1.Five diploma Celsius threshold as compared to the pre-business common set as the goal in the 2015 Paris Agreement for proscribing warming.

It isn't simply that there has been a new document worldwide temperature – that become to be predicted; a medium-sturdy El Niño supplemented by means of the decadal developments related to the inexorable upward thrust in greenhouse gases intended that we would anticipate new records for temperature for some months in 2023.

It is the margin via which the record changed into broken and broken month after month for an entire yr. We may even track the month-to-month increment. It reached its maximum value in September 2023 when the boom turned into more than 0.5 ranges Celsius above any preceding September.

It might be as though, during the last fifty years the report for the guys’s hundred-meter sprint were broken via a tenth of a second every five or ten years. And a runner has now arrived who has broken the preceding document by using 1/2 a 2d.

What’s Inflicting the Rise?

There needs to be a reason and a purpose. What precipitated this bounce in worldwide temperatures? Was the 2023 El Niño particularly severe? Maybe the pool of warm water stretched out throughout the equatorial Pacific turned into specially deep, huge, or hot? Yet as measured by means of temperature or depth or width, El Niño does now not seem specifically unusual.

Read Also: Alphabet Reassigns Two Veteran Access Executives as Slim Down of Division Continues

Could it had been that massive submarine eruption in Tonga in January 2022 which injected a hundred and fifty million tons of water vapor and sulfate aerosols into the middle stratosphere? The water vapor is a greenhouse gas anticipated to boom the downward infrared radiative flux, even as the aerosols lessen sun radiation.

However, a hard and fast of models suggests that the effect of the aerosols have to outweigh the water vapor. Another have a look at suggests a modest growth in warming with the aid of zero.0.5°C over the subsequent five years.

The Tonga eruption does now not look to provide the answer. The offender appears to be someplace else completely: ships’ funnels and the final results of the International Maritime Organization (IMO) regulations on sulfate emissions.

Shifting to Low Sulfur Transport Fuels

Sulfate emissions are linked to the sulfur content material of deliver fuels, and heavy gasoline oil (HFO) with a tar-like consistency has powered delivery for seventy or extra years. Cheaper than different fuels, HFO, additionally called bunker gas or residual gasoline oil, is the result or remnant of the petroleum distillation and cracking process.

The IMO goals to lessen sulfur dioxide emissions by 75 percent, and regulations had been progressively tightened, moving far from HFO with a maximum content of three.Five percent to lower sulfur fuels along with marine gasoline, which consist completely of distillates.

The sulfur content of fuels was limited to 1 percent in North Atlantic coastal regions in 2010, then decreased to 0.1 percentage in 2015. In 2020, a worldwide restriction was located of zero.5 percentage. Sulfur dioxide emissions from fossil fuels have lengthy contributed to intense health influences by forming particulate count number called PM2.5.

Read Also: What Type of Solar Panel Should You Choose?

The previously excessive sulfur content material of marine fuel – a lot higher than degrees allowable on land, and focused sulfate emissions from busy transport ports and routes in areas consisting of India and China have proved harmful to the ones residing in neighboring groups.

A study in 2018 confirmed that before purifier shipping fuels, ship-associated health impacts blanketed ~four hundred,000 premature deaths from lung cancer and cardiovascular disorder and ~ 14 million youth bronchial asthma cases yearly.

Less harmful emissions as a result of the switch faraway from HFO to lower sulfur fuels for delivery, with a bit of luck result in much less struggling in phrases of fitness impacts for coastal communities.

So a long way, so accurate. So, why are sulfate emissions important when looking at file-rising temperatures? It is due to the fact sulfate emissions provide the nuclei for condensation and cloud formation, generating ‘whitetop’ clouds with higher albedo – capable of reflect sunlight that produces a cooling effect.

The greatest effect from this is where there are the most ships – inside the northern Atlantic and north Pacific. With the IMO rules coming in, after 2015 deliver smoke ‘tracks’ have been discovered to be substantially reduced.

By 2020, ship tracks had more than halved, and sulfur dioxide emissions from delivery plummeted by around eighty percentage. Such a rapid discount in sulfur emissions must correspond with a fast discount within the cooling effect generated by using the improved reflective characteristics of the clouds.

One examine confirmed that switching to low-sulfur fuels reduces the radiative cooling effect from deliver aerosols with the aid of around 80 percentage.

This equates to around a 3 percent boom in cutting-edge estimates of general anthropogenic forcing. From January 2015 to December 2022 global absorbed sun electricity had accelerated by means of 1.05 watts/m2 relative to the preceding suggest. This impact is a whole lot extra than were predicted.

However, now that sulfate aerosols were decreased, can global temperatures be expected to upward push faster than was previously expected? The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) reviews have converged on a weather sensitivity of three levels Celsius for a doubling of carbon dioxide, alongside cloud feedbacks and probably positive assumptions for a way excess warmth passes into the deep ocean.

Related Article: What Is Elon Musks Hyperloop Tunnel?

However, research of the Ice Ages and the hyperlink between international temperatures and carbon dioxide tiers recommend a 4.Eight degrees Celsius increase for a doubling of carbon dioxide implying that the contribution of decreased aerosol forcing is more terrible than the exceptional estimates of the IPCC.

This is awful information, implying that the rate of boom in temperatures visible through 2023 becomes the new ordinary. No one appears too keen on restoring the polluting ship’s gasoline. That would imply our projections for 2050 end up what occurs by way of 2035, that is awful information for groups, corporations, farmers, and insurers viewing the impacts on vegetation and flash floods within the faraway future.

Aerosol cloud interactions continue to be the largest area of uncertainty in projected temperatures. However, the ships’ smokestacks have proved that raising atmospheric aerosols should one day grow to be a fundamental means of slowing further temperature rises.